New Idea for Battery Manufacturing: A Simple Press to Accelerate Electrolyte Wetting

Press & Wet: A “Sponge-Inspired” New Strategy for Pouch Battery Electrolyte Wetting

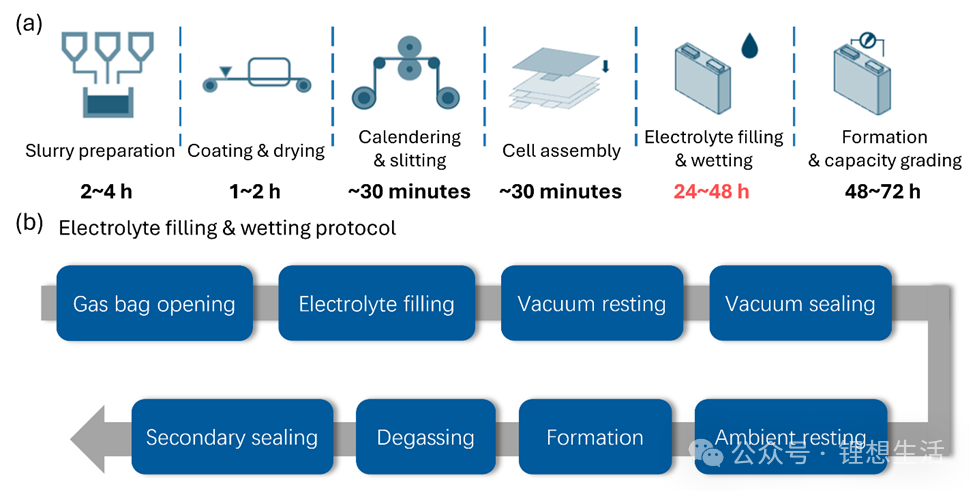

In the manufacturing process of lithium-ion batteries, electrolyte injection and wetting is an often-overlooked yet crucial step. The electrolyte must fully penetrate the separator and the interior of porous electrodes to form stable ion-conducting pathways, providing an efficient and safe operating environment for the battery. However, the electrolyte wetting process is typically extremely slow—even in automated production lines, it often takes 24 to 48 hours to complete. This not only severely slows down the production rhythm but also significantly increases manufacturing costs.

A research team from The University of Texas at Austin has ingeniously proposed a new idea inspired by daily life: “Just like squeezing a sponge, give it a press to let the electrolyte ‘seep’ in on its own.” This strategy shortens the traditionally lengthy wetting time from tens of hours to less than 1 hour, offering a brand-new path to speed up battery manufacturing.

Battery Manufacturing “Bottleneck”: The Anxiously Slow Wetting Process

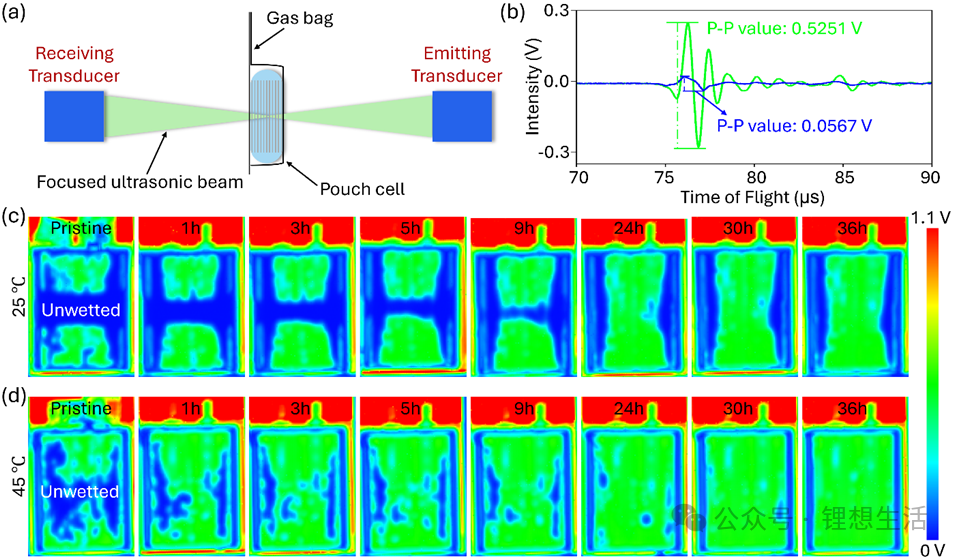

Figure 1 shows the typical manufacturing process of lithium-ion batteries. From slurry preparation, coating, calendering and slitting to assembly, electrolyte injection and formation, every step is crucial. In the battery manufacturing process, although the formation step is more time-consuming, it is often the seemingly simple “waiting for wetting after electrolyte injection” that truly slows down the production rhythm.

When the electrolyte is injected into the cell, it needs to gradually penetrate into each layer of material through the porous electrode structure. This process is affected by various factors such as capillary force, surface tension, viscosity and pore size distribution, and usually takes dozens of hours to complete. If wetting is insufficient, the electrolyte cannot fully contact the electrode surface, which will lead to uneven formation of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) film, increased internal resistance, shortened cycle life, and even local overheating and safety risks.

Therefore, how to accelerate the “wetting” speed of the electrolyte inside the electrode has become one of the key technical problems restricting the efficiency of the battery industry.

Attempts to Accelerate Wetting: From Heating to Vacuum, Results Still Fall Short

To shorten the wetting time, the scientific and industrial sectors have tried a variety of methods. A common approach is heating: by increasing temperature to reduce the electrolyte’s viscosity, thereby speeding up its penetration. Experiments show that raising the ambient temperature from 25°C to 45°C does accelerate electrolyte infiltration. However, the effect remains limited—even at 45°C, wetting still takes nearly 30 hours to complete. What’s more, excessively high temperatures can accelerate electrolyte decomposition, posing safety risks.

Another strategy is vacuum-assisted wetting, which lowers air pressure to help the electrolyte enter microporous structures more easily. While this method improves initial wetting efficiency in experiments, it comes with high equipment costs and is difficult to scale up. In addition, researchers have explored enhancing wettability through electric fields (electrocapillary effect), laser microchannels, electrolyte additives, and other means. Yet these methods generally suffer from issues like complex operation, high cost, or poor adaptability.

After analyzing these approaches, the team realized that to fundamentally speed up wetting, a new solution—simple, physically driven, and scalable—was needed.

Inspiration from Daily Life: From “Squeezing a Sponge” to “Pressing a Battery”

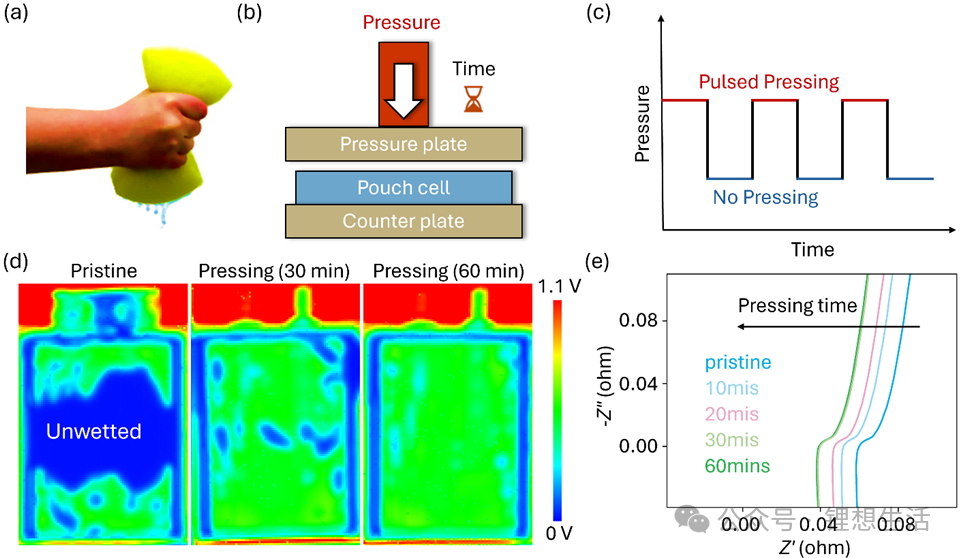

In daily life, we all know that a sponge absorbs water very slowly when left at rest, but with just a few gentle squeezes, water can be quickly drawn in and evenly distributed. Drawing inspiration from this phenomenon, the team wondered: Could periodic mechanical pressing help “suck” electrolyte into porous electrodes just like water into a sponge? They thus proposed a “pulsed pressing” strategy. As the name suggests, it involves applying intermittent mechanical pressure to pouch batteries during the wetting process, using a cycle of “press—release—press—release” to drive the electrolyte to flow, disperse and be adsorbed within the porous structure.

The core of this strategy lies in the regulation of frequency and pressure. Excessively high pressure may damage the internal structure of the battery cell, while excessively low pressure makes it difficult to generate significant flow. After numerous experiments, the team determined an optimal balance that balances safety and efficiency: a pressing force of approximately 10 kPa and a high-frequency mode of 0.5 seconds of pressing followed by 0.5 seconds of rest.

To intuitively verify the effect of the pressing strategy, the research team used two methods—ultrasonic transmission imaging and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)—to monitor the wetting process in real time. Ultrasonic imaging, similar to “having a B-scan”, allows direct visualization of electrolyte penetration inside the battery cell. Unwetted areas appear blue, while wetted areas appear green. Experimental results show that under the high-frequency pressing mode, most blue areas turned green after only 30 minutes; by 60 minutes, the entire cell was fully wetted. In contrast, the control group, left standing at room temperature, was still not fully wetted even after 40 hours.

EIS tests further confirmed this. During the pressing process, the cell’s high-frequency resistance (HFR) dropped rapidly and stabilized within 1 hour, indicating that the electrolyte had fully filled the pores, forming continuous ion channels with reduced impedance. In comparison, the HFR of the non-pressed group took nearly two days to decrease to a similar level.

Interestingly, the study also found that the frequency effect of pressing is very significant. When using a low-frequency mode (5 minutes of pressing / 5 minutes of rest), although wetting was improved, it was still difficult to complete in a short time—proving that high-frequency cycles are the key to promoting rapid liquid penetration.

Not Only Faster, But Also More Stable: Performance Remains Uncompromised

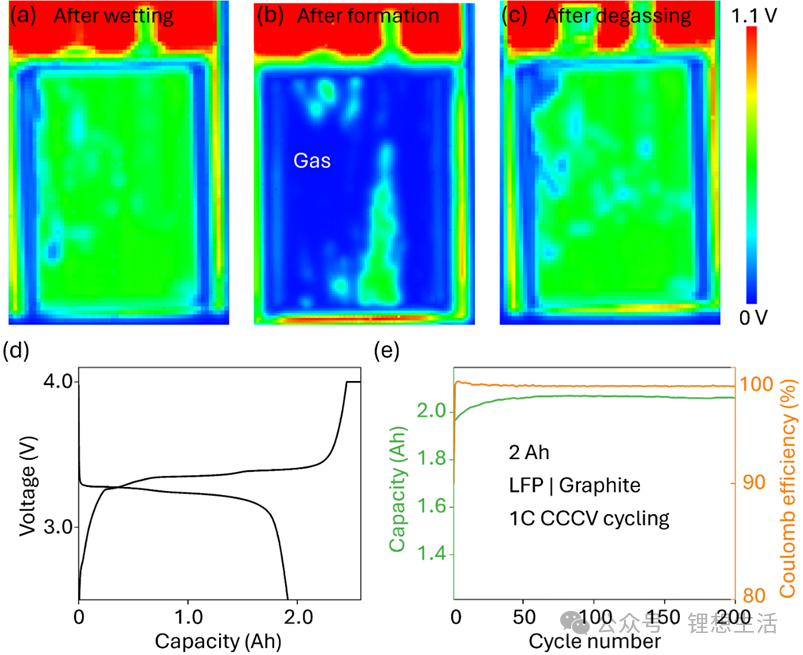

Speeding up the wetting process is just the first step; the more critical question is whether such “mechanical intervention” will damage battery performance. To verify this, the team conducted standardized electrochemical tests on 2 Ah LiFePO₄–graphite pouch cells wetted via pressing.

The results showed that their charge-discharge curves were identical to those of cells fabricated using traditional methods, with a discharge capacity of approximately 2 Ah and an initial cycle Coulombic efficiency as high as 98.4%. After 200 charge-discharge cycles at 1C, the battery capacity showed almost no degradation, demonstrating excellent cycle stability. This indicates that pressing-accelerated wetting not only did not damage the internal structure but also maintained high consistency and long-cycle-life performance.

Figure 4 further presents ultrasonic images of the cells after formation, degassing, and secondary encapsulation. It can be seen that the electrolyte was uniformly distributed, with no local dry areas or bubble accumulation—proving the controllability and repeatability of this strategy.

Figure 4: Excellent Electrochemical Performance Maintained After Press-Accelerated Wetting

Simple, Scalable, and Industry-Friendly: Turning “A Simple Press” into a Manufacturing Tool

Unlike complex electrode modification or vacuum systems, the pulsed pressing method does not require changing any battery materials or structures. It only needs to add a programmable mechanical pressure regulating device during the wetting stage. For pouch batteries, their inherent flexibility makes them highly suitable for this mechanical modulation. For prismatic or cylindrical batteries, future adaptation can be achieved through the design of external fixtures or local elastic packaging.

More importantly, this method is fully compatible with existing production lines, featuring low cost and simple operation, thus boasting enormous potential for industrial promotion. In the future, combined with automated control and real-time ultrasonic monitoring, it may even form a closed-loop control system of “wetting—detection—pressure regulation”, realizing truly intelligent cell manufacturing.

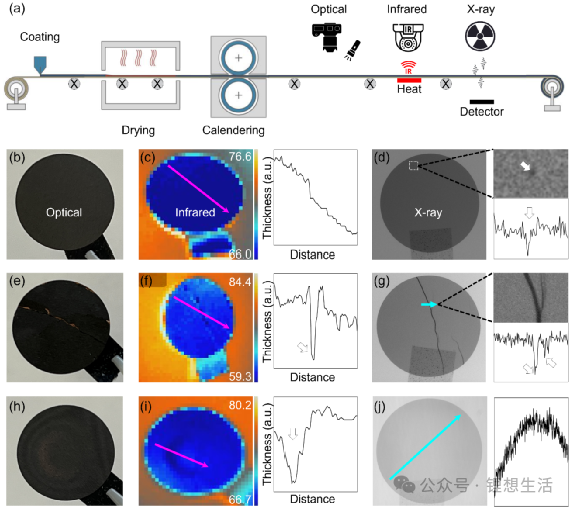

Previously, the team also proposed a multimodal characterization method combining optical imaging, infrared thermal imaging, and X-ray imaging to systematically identify defects in graphite anode coating layers. This method enables the collaborative detection and classification of surface and internal defects, providing strong support for electrode defect screening, quality control, and process optimization.

Figure 5: Multimodal Detection of Defects in Graphite Electrodes. (a) Multimodal characterization of electrodes during manufacturing via optical, infrared, and X-ray technologies. (b) Optical characterization of a graphite electrode with a smooth and uniform surface. (c) Infrared characterization of a graphite electrode with a smooth and uniform surface. (d) X-ray characterization of a graphite electrode with a smooth and uniform surface. (e) Optical characterization of a graphite electrode with surface cracks. (f) Infrared characterization of a graphite electrode with surface cracks. (g) X-ray characterization of a graphite electrode with surface cracks. (h) Optical characterization of a non-uniform graphite electrode. (i) Infrared characterization of a non-uniform graphite electrode. (j) X-ray characterization of a non-uniform graphite electrode. The diameter of the graphite electrode is 12 mm.

References:

1. Li, W.; Zhao, Z.; Yanyachi, A.; Kuppan, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Ezekoye, O.; Khani, H.; Liu, Y., Sponge-Inspired Pressing Approach to Facilitate Electrolyte Wetting in Li-Ion Pouch Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2025,172 (9), 090528.

2. Li, W.; Yanyachi, A.; Sun, T.; Wu, D.; Banis, M. N.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Kuppan, S.; Ezekoye, O.; Liu, Y., Multimodal Characterization of Coating Defects in Graphite Electrodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2025,172 (8), 080523.

Sourse: WeChat 锂想生活 https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/coVwqtFD7Yz23mzUfPmo_Q

Due to the limited knowledge and English level is inevitable errors and omissions, if there are errors or infringement of the text, please contact me as soon as possible by private letter, I will immediately be corrected or deleted.

Maybe you will be interested in:

5-Minute Guide to Neware Battery Testing System Charge/Discharge Steps