“Silent Alarms” in NCM Batteries: The Interplay Between Gas Generation, Battery Safety, and Battery life

During the battery formation stage—the final step before a brand-new NCM (Ternary) battery leaves the factory—the volume of gas discharged is enough to make any engineer frown with concern. These invisible gases are quietly dictating the battery’s future lifespan and its safety boundaries. As the market share of New Energy Vehicles (NEVs) surges, batteries now account for over 50% of a vehicle’s total cost, making safety and longevity the top priorities for consumers.

Ternary lithium batteries, particularly high-nickel systems, are widely favored for their high energy density. However, the gas evolution that occurs during cycling and storage remains a critical internal trigger for capacity degradation and potential safety hazards.

01 Micro-reactions: The Origin of the Gas

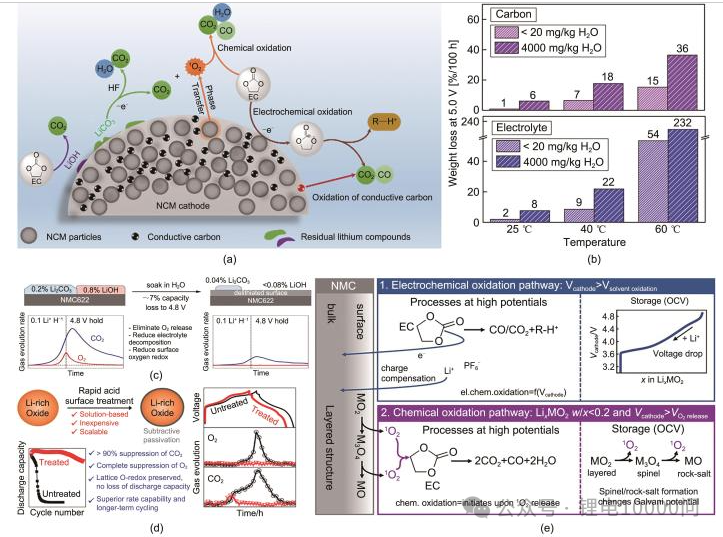

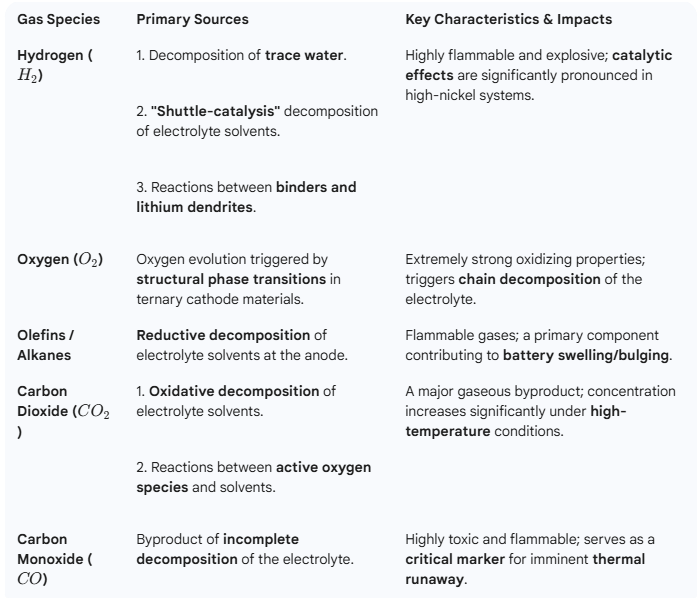

Side reactions at the interface between the electrolyte and the electrode materials are the primary source of outgassing. Mapping the “lineage” of these gases is the first step toward effective control. The gases produced by NCM batteries primarily consist of six types: hydrogen, oxygen, olefins, alkanes, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide.

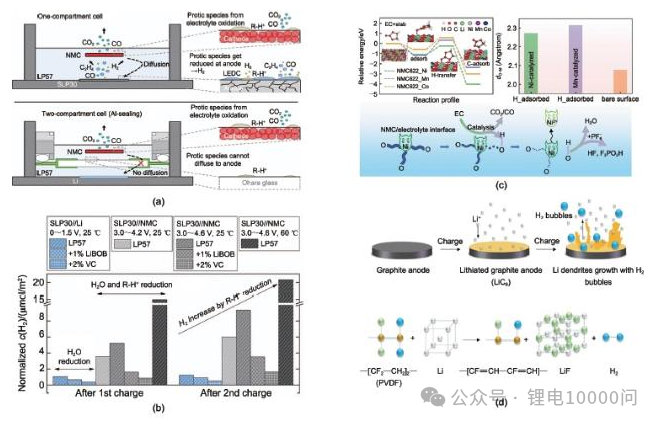

Hydrogen: The Most Ubiquitous Source Hydrogen has the most diverse origins. The most direct source is the decomposition of trace water—which can never be entirely eliminated from the battery—at the anode. However, a more significant pathway involves the electrolyte solvent: it oxidizes at the cathode surface to form protonated solvents, which then shuttle to the anode and are reduced to generate hydrogen. Research indicates that transition metals act as catalysts in this process, making hydrogen evolution particularly severe in high-nickel cathodes.

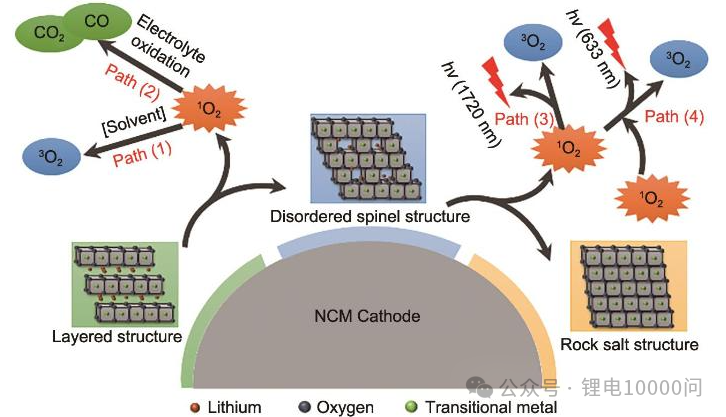

Oxygen: The “Endogenous” Gas of Ternary Materials Oxygen is a unique “endogenous” (internally generated) gas for NCM materials. Under conditions of overcharge, high temperatures, or prolonged cycling, the cathode material undergoes a structural phase transition—shifting from a layered structure to a spinel phase, and eventually to a rock-salt phase. This process triggers the release of lattice oxygen. These highly reactive oxygen species then “attack” the electrolyte, sparking a chain of decomposition reactions that produce large volumes of gases like CO2.

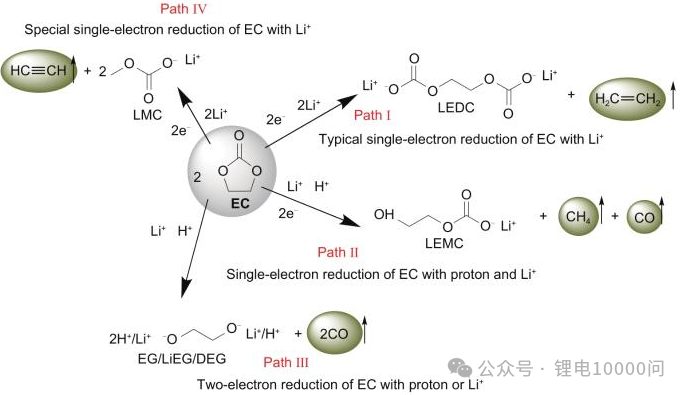

Hydrocarbons and Carbon Oxides: A Diverse Family The hydrocarbon family—primarily olefins and alkanes—results from the reductive decomposition of electrolyte solvents at the anode surface. In contrast, Carbon Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide are joint products of two processes: the oxidative decomposition of solvents at the cathode under high voltage, and the secondary reactions between released active oxygen and the solvent.

02 Performance Degradation: How Outgassing “Kills” a Battery

The impact of gas generation on battery performance is both progressive and fatal.

From a Macroscopic Perspective: The accumulation of gas causes battery swelling (bulging) and leads to the misalignment of electrodes and separators. This physical distortion increases polarization, resulting in rapid capacity decay.

From a Microscopic Perspective: Gas bubbles aggregate on the electrode surfaces, obstructing the essential contact between the electrolyte and the active materials. This leads to a sharp increase in internal resistance and a significant decline in charge-discharge efficiency. More importantly, the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) layer—the protective film on the electrode—continuously ruptures and reforms to repair the damage caused by outgassing. This process persistently consumes active lithium and electrolyte, which is one of the fundamental causes of shortened cycle life.

The Nexus Between Outgassing and Safety

The relationship between gas generation and safety is even more direct. The buildup of internal pressure is the direct mechanical force that triggers battery deformation, bulging, or even mechanical rupture.

Under thermal abuse conditions, the situation deteriorates rapidly. Research indicates that:

- Initial Stage: NCM batteries begin by releasing primarily small-molecule gases.

- High-Temperature Stage: At higher temperatures, the batteries continuously emit long-chain carbonaceous gases. Use Neware chamber test your batteries at high and low temperature.

These flammable gases mix with the oxygen released from the cathode to form a volatile “pre-mixed flammable gas” within the cell. Once exposed to a thermal hot spot or a spark triggered by an internal short circuit, it becomes highly susceptible to thermal runaway, leading to combustion or explosion.

03 The Safety Redline: The “Fatal Pathway” from Outgassing to Thermal Runaway

Thermal runaway is the ultimate nightmare for battery safety, with outgassing serving the dual roles of “accelerant” and “fuel source.” During a thermal runaway event, the gas venting behavior can be categorized into four distinct stages: Gas Incubation, Safety Valve Rupture, Accelerated Ejection, and Venting Termination.

- Gas Incubation Stage: Internal side reactions cause a gradual buildup of pressure.

- Safety Valve Rupture: Once the internal pressure breaches the safety vent, the high-speed ejection of flammable gases poses immediate risks of physical impact and combustion.

The Influence of Ambient Pressure

It is crucial to note that ambient pressure significantly alters outgassing characteristics and associated risks. Research has shown that:

- Trigger Timing: As ambient pressure decreases (e.g., at high altitudes), thermal runaway is triggered earlier.

- Absolute Severity: While the absolute intensity of high-temperature heat and gas impact may decrease in low-pressure environments, the chemical risk increases.

- Explosive Risk: In low-pressure settings, the vented gas contains a lower concentration of CO2 and a higher concentration of unsaturated hydrocarbons. This composition shifts the flammability/explosion limits, widening the range and making the gas mixture significantly more prone to explosion.

04 Electrolyte Engineering: Core Strategies for Suppressing Gas Generation

Since the electrolyte is the main reactant in gas generation, suppressing gas generation through electrolyte modification becomes the most direct strategy. The approach mainly revolves around two dimensions: improving the intrinsic stability of the electrolyte and constructing a robust electrode/electrolyte interface.

Eliminating the “Bad apples.” Trace amounts of water, acid, and reactive oxygen species evolved from the positive electrode in the electrolyte are the main culprits triggering chain reactions. Adding dehydrating additives and acid scavengers can eliminate the generation of harmful acidic substances at the source. More importantly, reactive oxygen species scavengers are used; they preferentially react with highly reactive singlet oxygen and other substances to form stable products, thereby preventing their chain oxidation of solvent molecules.

Building a “strong wall.” On the positive electrode surface, by adding positive electrode film-forming additives, a dense and stable positive electrode-electrolyte interface film is preferentially oxidized and formed in the early stages of cycling. This film can inhibit transition metal dissolution and prevent direct contact between the electrolyte and the highly active positive electrode surface, thereby significantly reducing oxygen evolution and solvent oxidation. On the negative electrode side, optimizing the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) film is equally important. Using additives such as fluoroethylene carbonate helps form a dense, mechanically strong, lithium-fluoride-rich SEI film, which more effectively inhibits the continued reductive decomposition of solvent molecules and reduces the generation of olefin and alkane gases.

Upgrading the “basic materials” is crucial. Developing and using novel solvents and lithium salts is a fundamental solution. For example, replacing traditional carbonates with partially fluorinated solvents can significantly improve the electrolyte’s antioxidant potential and thermal stability. Reducing the proportion of cyclic carbonates or using more stable solvents such as linear carboxylic acid esters can also reduce reduction gas production at its source.

05 Process and System Defense Line: End-to-End Control from Manufacturing to Monitoring

Besides improvements in materials themselves, manufacturing processes and system design are also crucial.

In battery manufacturing, negative pressure formation is a key process. Advanced stepped negative pressure design, by matching the different stages of bubble generation, merging, and discharge through step-by-step pressure reduction, can more efficiently remove nascent gases, preventing gas retention from affecting wetting and subsequent performance.

At the battery user end, establishing early gas warning systems is a cutting-edge direction. Since gas generation often precedes significant changes in voltage and temperature, real-time or online monitoring of the gas composition and pressure inside the battery can achieve earlier warnings of thermal runaway. Deploying sensors to monitor the total amount of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, hydrogen fluoride, and combustible gases in high-risk areas such as the formation and capacity workshop and electrolyte warehouse, and interlocking them with the ventilation system, is a basic requirement for factory safety.

Looking to the future, research on gas generation in ternary batteries is moving towards precision and intelligence. By utilizing advanced techniques such as differential electrochemical mass spectrometry, online analysis of gas escape at different cycling stages can more accurately correlate gas production with performance degradation. Combined with artificial intelligence algorithms, by learning from historical gas production data, the remaining battery life and potential risks can be predicted, potentially enabling a shift from “post-event remediation” to “pre-event prevention.”