When the electrolyte fails to reach every microscopic corner of the battery uniformly, performance degradation and safety risks quietly lurk. The energy density, lifespan, and safety of lithium-ion batteries are inseparable from the uniform and sufficient ‘wetting’ of the electrolyte within the cell.

The process is akin to rainwater seeping into the soil—it must penetrate deeply enough and distribute uniformly. However, as cell designs become increasingly complex and energy densities continue to rise, this seemingly simple ‘wetting’ process has evolved into a critical bottleneck restricting battery performance.

What is Electrolyte Wettability?

In essence, electrolyte wettability is the ability of the electrolyte to penetrate and spread through porous media, such as electrodes and separators. You can visualize it as water soaking into paper or a sponge: the speed and uniformity of this infiltration determine whether the subsequent electrochemical reactions can proceed effectively.

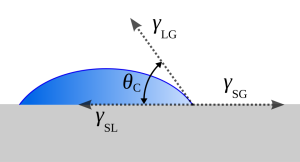

The core physical parameter for measuring wettability is the contact angle(θ). When a droplet of electrolyte is placed on an electrode surface, the angle formed between the edge of the droplet and the solid surface is the contact angle.

- A smaller angle indicates better wetting and easier spreading.

- A larger angle signifies poorer wettability and greater resistance to infiltration.

This simple parameter serves as the primary yardstick for evaluating and optimizing the interfacial compatibility between the electrolyte and electrode materials.

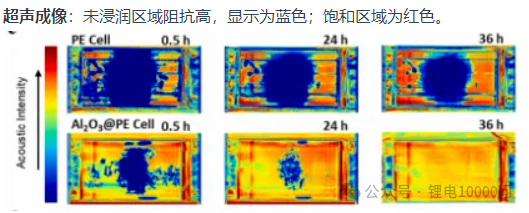

Ultrasonic Imaging: Areas with poor infiltration exhibit high acoustic impedance and are displayed in blue; saturated regions are shown in red.

However, wetting is more than just a surface phenomenon. Inside the cell, the electrolyte must undergo three-dimensional penetration through the complex and tortuous microscopic pores of the electrodes and separators. The speed and uniformity of this process ultimately determine the structural quality of the ion transport network.

The “Invisible Hand” of Wettability

The penetration behavior of the electrolyte within the cell is synergistically influenced by the following two factors:

The intrinsic properties of the electrolyte are the decisive internal factors.

Surface Tension and Viscosity: Surface tension determines the liquid’s ability to overcome its own cohesive forces, while viscosity reflects the internal resistance to flow. Generally, electrolytes with low viscosity and low surface tension possess better fluidity and can more easily infiltrate micropores. To balance these properties, mixed solvent systems such as EC/DMC are commonly used in practice.

Component Characteristics: The types of solvents, lithium salts, and additives all impact wettability. For instance, specific surfactant-type additives can significantly reduce the interfacial energy between the electrolyte and the electrode, thereby improving wetting.

The structure of the electrode and the cell constitutes the external constraints.

- Electrode Material Surface Characteristics: The low surface energy of graphite anodes makes them naturally lyophobic (liquid-repellent), which is a key challenge to overcome. The morphology, particle size, and compaction density of electrode materials are also critical. Excessive compaction density significantly reduces electrode porosity, creating physical barriers to electrolyte penetration.

- Cell Structural Design: Due to their dense winding structure, large cylindrical batteries force the electrolyte wetting process to shift from macroscopic flow to slow penetration driven by capillary action, presenting a massive challenge. During battery operation, areas with high current density and temperature, such as the tabs, are more prone to “dewetting”—a phenomenon where the electrolyte is consumed or becomes unevenly distributed.

How to Improve Electrolyte Wettability?

In response to the factors mentioned above, the industry has developed multi-dimensional improvement strategies across material, process, and system engineering levels.

Material Innovation: Optimizing Intrinsic Properties

The most direct approach is to adjust the physicochemical properties of the electrolyte at its source.

- Utilizing Low-Viscosity Solvents: Partially replacing traditional carbonates with short-chain carboxylates (such as EA or EP) can significantly enhance fluidity at low temperatures, providing a foundation for rapid infiltration.

- Developing Specialized Wetting Agents: Adding trace amounts of high-efficiency surfactant-type wetting agents can directly reduce the contact angle between the electrolyte and the electrode sheets. Research reports indicate that this can markedly improve overall wetting efficiency.

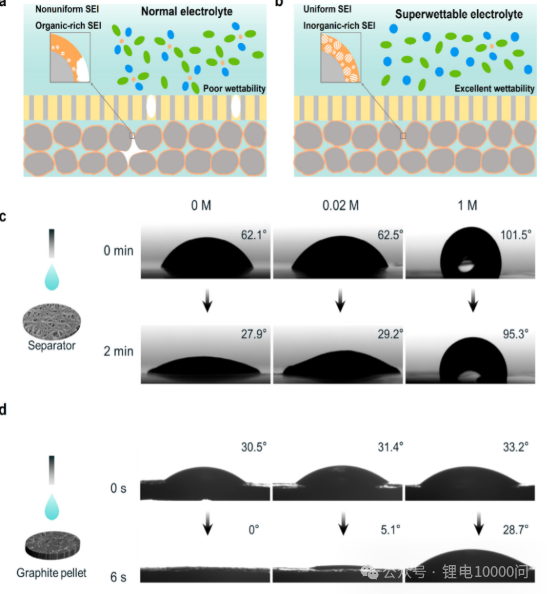

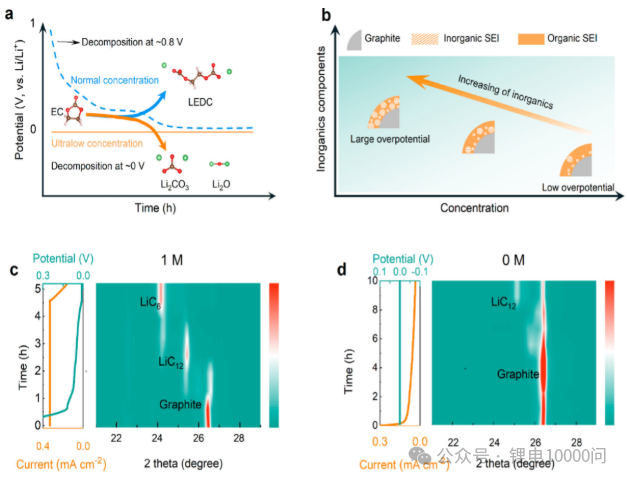

- Regulating Electrolyte Concentration: An innovative approach proposed by research teams involves using an “ultra-low concentration” electrolyte during the initial battery formation stage. This type of electrolyte features extremely low viscosity and excellent wettability, which induces the formation of a more uniform and stable Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI), laying the groundwork for subsequent high-performance cycling.

Process Innovation: Breaking Through Infiltration Barriers

By optimizing manufacturing processes, the infiltration challenges posed by complex electrode structures can be effectively overcome.

- Vacuum Filling: This is currently the most critical process. By evacuating the air inside the cell to create a vacuum, gas resistance is minimized, making it easier for the electrolyte to penetrate micropores.

- Segmented Wetting and External Force Application: For pouch cells, specific directional pressure can be applied via clamping plates after injection, or rolling techniques can be used to actively expel bubbles and promote electrolyte distribution.

- Deep Degassing: More refined processes employ “segmented wetting,” which involves secondary vacuum cycles during the aging period to expel bubbles trapped deep within the structure.

System Matching and Collaborative Optimization

A higher-level solution involves systematically matching cell design with electrolyte characteristics. For example, when designing the pore structures of thick electrodes or high-energy-density cells, one must pre-calculate the wetting properties of the chosen electrolyte. In some cases, this leads to the “custom development” of exclusive electrolyte formulations tailored specifically to a particular cell architecture.

How Infiltration Dictates Battery Fate

Whether electrolyte wetting is sufficient and uniform directly impacts battery performance across multiple dimensions.

1. Performance Dimensions

The most immediate consequence of insufficient wetting is reduced usable capacity and increased internal resistance. Active materials not covered by the electrolyte become “islands”—unable to participate in electrochemical reactions. This results in an actual battery capacity that falls significantly below its design value.

2. Interface Stability and Cycle Life. How to test battery cycle life? Neware battery cyclers

Uniform wetting is a prerequisite for forming a stable Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) film. Non-uniform infiltration leads to localized excessive current density, triggering uneven lithium deposition or even the formation of lithium dendrites. This not only consumes active lithium and accelerates capacity fade but also poses severe safety hazards. Furthermore, uneven interfacial reactions accelerate the rupture and reconstruction of the SEI film, continuously depleting the electrolyte and compromising cycle life.

3. Safety Risks

“Dry zones” or areas with inadequate wetting obstruct ion transport, which can lead to localized overheating—a primary trigger for thermal runaway. Over long-term cycling, the accumulation of non-uniform wetting and the resulting side reactions significantly increase the overall risk of battery failure.

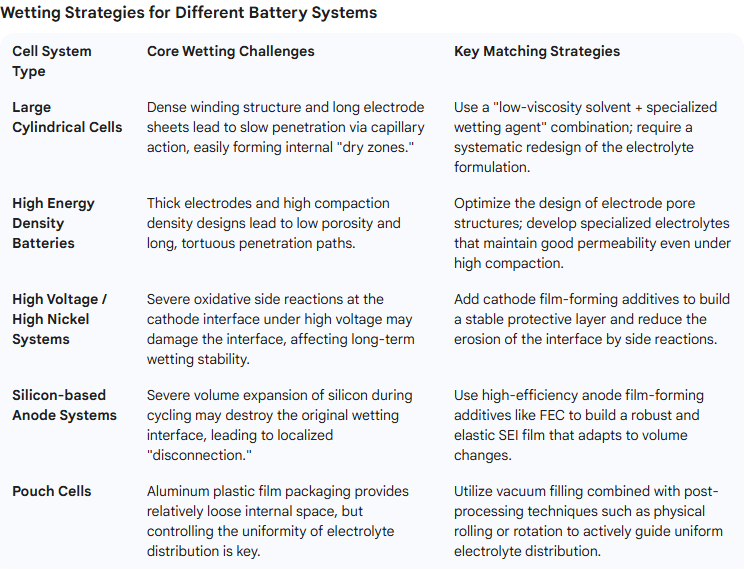

Wetting Strategies for Different Cell Architectures

As different cell systems face distinct wetting challenges and optimization strategies due to their diverse materials and structural designs, the key challenges and matching strategies for various cell types are summarized below:

Future Outlook

In the future, the research and optimization of electrolyte wettability will evolve toward greater precision, intelligence, and fundamental understanding.

On one hand, with the development of solid-state and semi-solid-state batteries, the issue of wettability will transition into a solid-solid interface contact problem, requiring entirely new interface engineering technologies and material solutions.

On the other hand, the optimization of wettability will increasingly rely on multiscale simulation and advanced inspection technologies. Computer simulations can proactively predict the penetration behavior of electrolytes within specific cell designs. Meanwhile, non-destructive imaging technologies—such as ultrasonic scanning and X-ray CT—will act like “X-ray vision,” allowing for real-time monitoring of electrolyte distribution and changes during battery manufacturing and operation. This enables the precise localization of “dry zones” and achieves closed-loop quality control.